To meet California’s energy efficiency and greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction goals, the current trends, modeling tools and challenges of adopting low global warming potential (low-GWP) refrigerants in the supermarket/grocery sector must be understood. We investigated the impact of phasing out the hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerants in a recent study of the commercial refrigeration market to characterize these key areas. Under an emerging technology project for SCE, the study surveyed industry stakeholders nationwide, and analyzed existing refrigeration equipment adoption to determine important factors for adopting low-GHG refrigeration options.

Next week I will share the study results at NASRC’s Sustainable Refrigeration Summit. I’m lucky to be joined by folks from the CPUC, SCE, VEIC and NASRC where we’ll discuss the nexus of issues around energy efficiency, low-GWP refrigerants, and how to meet California’s emissions goals. That discussion should be an interesting one and I urge you to sign up and join in (register here).

In the meantime, here are some of the key take-aways from the study:

- Increased adoption of low-GWP refrigerants in existing stores (aka market turnover) will be necessary to meet our emissions targets – business as usual rates of adoption won’t get us there.

- Workforce education and training will be important to install and service new systems.

- Industry stakeholders could use additional tools to model the energy and GHG impacts of system designs

The report also summarizes California’s current policies that are driving changes in HFC phaseouts and energy efficiency regulations.

You’ll find some key details on the study’s methods and findings below, but for more, download the full report free at https://www.etcc-ca.com.

Stakeholder Feedback

In the study we interviewed stakeholders representing more than 1,000 grocery stores in California, as well as engineers, consultants, policy makers and manufacturers that serve the state and other U.S. markets. Their feedback established the study’s approach to market projections and confirmed assumptions about the state of low-GWP adoption.

As well as providing feedback about the use of modeling tools (see below), stakeholders confirmed that transition to low-GWP refrigerants will likely follow simple trends:

- New construction has and will include some exploration of low-GWP systems, but primarily as “pilots” to gain experience.

- For most chains, new construction of low-GWP stores will be driven by code requirements. However, one European-based chain in California is ahead of this trend, adopting CO2 trans-critical systems as their prototype store design already.

- Most chains will choose to convert existing stores to “intermediate-GWP” options like R-448a and R-449a as relatively low-cost alternatives to lower average fleet GWP.

- Most chains will only do “gut rehab” replacements of systems to low-GWP options as systems age and are retired as part of the normal market turnover.

In discussions with stakeholders, it’s apparent that workforce education and training on new technologies will be a key factor in adoption. Currently there is a lack of service and equipment infrastructure to meet an increased need for these systems. However, stakeholders also pointed out that the timing of training for technicians is important – training that occurs too far in advance of experience in the field isn’t helpful. So, coordination and timing will be key.

Refrigeration System Modeling Tools

There are a few tools available to analyze the energy impacts of refrigeration system design. However, stakeholders find them too difficult to use as part of the normal design cycle, and design engineers generally do not use them for most stores. Survey results indicate that potential users would like modeling tools that:

- Are fast and easy to use (perhaps including template store and case designs).

- Can model whole-building interactive effects (e.g., impacts of humidity and HVAC on refrigeration loads).

- Can accurately model the diversity of new technology and low-GWP options (such as CO2 transcritical booster, vs. parallel system designs, and new refrigerant options).

The study used one of the tools investigated, Pack Calculation Pro, to assess the energy impacts of system efficiency for various refrigerant options. The report includes the energy efficiency ratio (EER) of various system types and refrigerant options in the state. However, system efficiency was not the focus. The study used them to roughly calculate energy consumption while comparing the indirect contribution to GHG emissions from energy use to direct emissions from refrigerant leaks.

Market Impacts and GHG Reduction Trends

The study used a top-down algorithm to estimate the impacts of multiple system types and market turnover due to remodels, retirements, and new construction in California’s grocery sector. To estimate the prevalence of system types, the study used California Air Resources Board (CARB) data supplemented with other sources to estimate stores that CARB doesn’t track (zero- and low-GWP systems). The study paired this data with stakeholder input to estimate replacements and remodels and project emissions totals due to direct and indirect GHG emissions. The study’s estimates of base-case emissions per year aligned well with CARB’s estimates of equivalent CO2 emissions to date.

Based on that modeling, the study made the following conclusions:

- California will likely not meet its GHG reduction goals on time. The state’s goal is to decrease HFC direct emissions to 40% of 2013 levels by 2030 (SB 1383).

- Increased turnover of existing store refrigerants will be needed to meet those goals.

- “Gas only” retrofits of intermediate-GWP refrigerants such as hydro-fluoro-olefins (“HFO”) blends will also not meet goals.

- A significant increase in turnover rates for existing stores to low-GWP options will be necessary to meet those goals

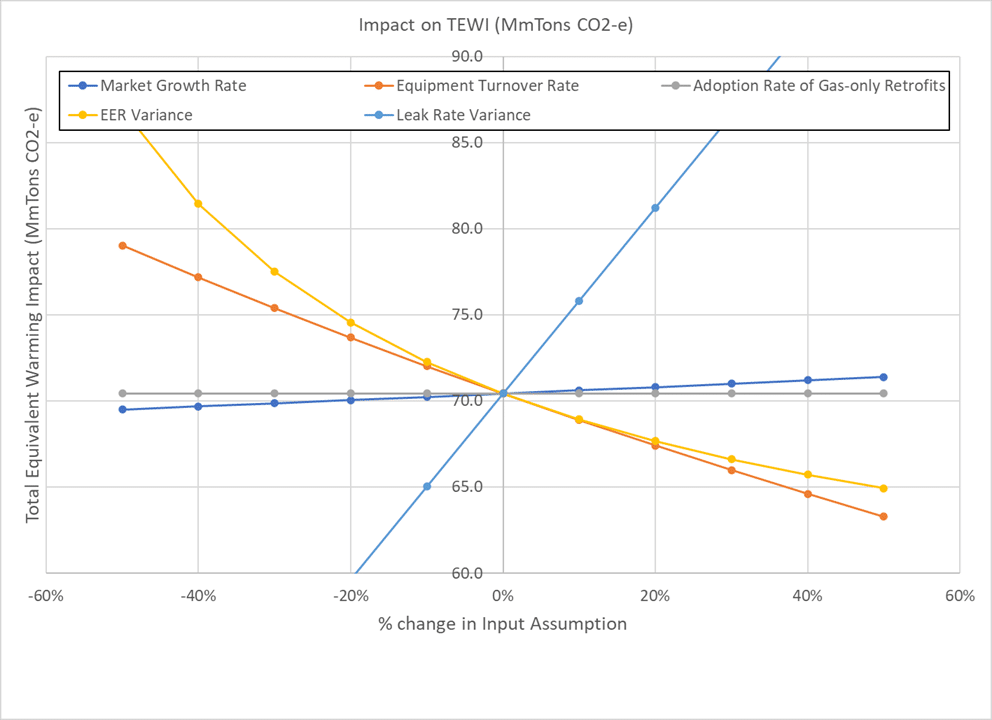

The following chart summarizes the sensitivity of some of the market model driving assumptions. The graph indicates the projected 20-year total equivalent warming impact (TEWI) and the center point (point of intersection) shows the baseline assumptions.

The individual lines show the relative impact of changing those assumptions.

The lines with the steepest slope indicates the variables that have the greatest impact on the results when you vary them.

The leak and turnover rate assumptions show the greatest impact on reducing TEWI.

The variance in EER, or system efficiency, is also significant, although large percentage changes are very difficult to achieve – we don’t have as much control over system efficiency as we would hope.

Increasing Low-GWP Refrigerants

How to achieve greater turnover is the key, unanswered question resulting from our study. While CARB made some funding available to accelerate adoption of low-GWP refrigerants, to date demand exceeds funding. The first day CARB opened the initial $1M project funding opportunity, it was fully committed by participants.

Another important area of upcoming research is the energy consumption of new system types. While the tools used by the study do an adequate job of estimating the energy consumption the purpose of assessing overall market impacts, they have yet to be verified with actual performance data by objective, third party evaluation of installed sites. That work will be important and will be captured by at sites participating in CARB’s F-gas Reduction Incentive Program (FRIP).

There’s much more in the study report, so I invite you to check it out. Let me know if there is more that you’d like to know about the data, our approach, or conclusions.

Kudos

My thanks go out to Paul Delany (SCE, now retired) for his leadership on this project, Jay Madden (SCE, Emerging Tech) for getting the report over the goal line, and Danielle Wright (NASRC) for initial concept, review, and comments on the findings. It’s a great honor and pleasure to get to work on research projects like this and I’m enormously grateful to Paul and Dani for their leadership in getting this project off the ground.