In 1982, an explosion of a Gasprom pipeline in Siberia was the first cyber-attack of an Industrial Control System (ICS). Stuxnet (the malware that took down Iran’s nuclear centrifuges) was released 10 years ago. According to Joe Weiss, an ICS cybersecurity expert, who recently wrote a brief history of ICS cybersecurity, it has been a growing, yet largely-ignored issue for 35 years.

Are Building Controls the Next Cyber Extortion Target?

Most of these early attacks (e.g. Stuxnet) were by nation-states who have the resources and motivation to perpetrate these events. And cyber technology has trickled down as the resources have gotten easier and cheaper to procure. Cyber criminals been targeting smaller organizations, including production facilities and small businesses. (Krebs on security recently wrote an article about how the main targets of cyber thieves are individuals and small business. Wired’s summary of cybersecurity events in the first half of 2017 shows that many of events included extortion for data.) Today we have Flame malware, which looks for engineering drawings, specifications, and other technical details, and even gathers information outside the computer by recording Skype calls, snaring Bluetooth devices, taking screenshots, and logging keystrokes. Triton/Trisis and Irongate, the next generation of industrial control system malware that have targeted factories and refineries. And let’s not forget when BART got hit with ransomware. Are control systems for our buildings next?

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) lumps building control systems and components together with ICS because they rely on PLCs and their control protocols are similar. ICS and Building Control system attacks have become so serious that the DHS has created a separate department just to deal with threats against these systems. This department, known as the ICS Cyber Emergency Response Team (ICS-CERT), reports on known attacks as well as known vulnerabilities in ICS/BCS systems. Since its founding in 2017, ICS-CERT has reported nearly 1000 vulnerabilities and attacks in these systems. Attacks have become so frequent that Kaspersky Labs, the largest ICS Malware Security provider, recently reported over 50% of their customers had suffered at least one ICS attack in the past 12 months.

We intend to keep our clients from suffering similar fates. Therefore we need to do all we can to protect their infrastructure – from Building Automation Systems (BASs) to lighting control systems, and even electrical distribution components. It is not a matter of if, but a matter of when, clients will suffer an attack. Like liability from Legionella, design engineers could be held liable if a cyber-attack causes harm to building occupants. Conditions that seem benign, such as turning off all the lights, could result in an unsafe conditions as people try to leave the building. And more severe situations could be caused, for example, by turning off ventilation to a chemical room, allowing harmful fumes to spread in a building.

What We Can Do to Prevent Cyber-attacks on Building Controls

So what are we to do? The first step is to realize that an attack is inevitable and include measures to prevent a breach, mitigate the impact, and recover following an attack. The next step is to take action. Here are some very practical ways you can help your projects/facilities stay safe.

Actions Designers Can Take

Designers need to consider cyber-attacks early in the design process with an emphasis on prevention, mitigation and recovery.

Prevention

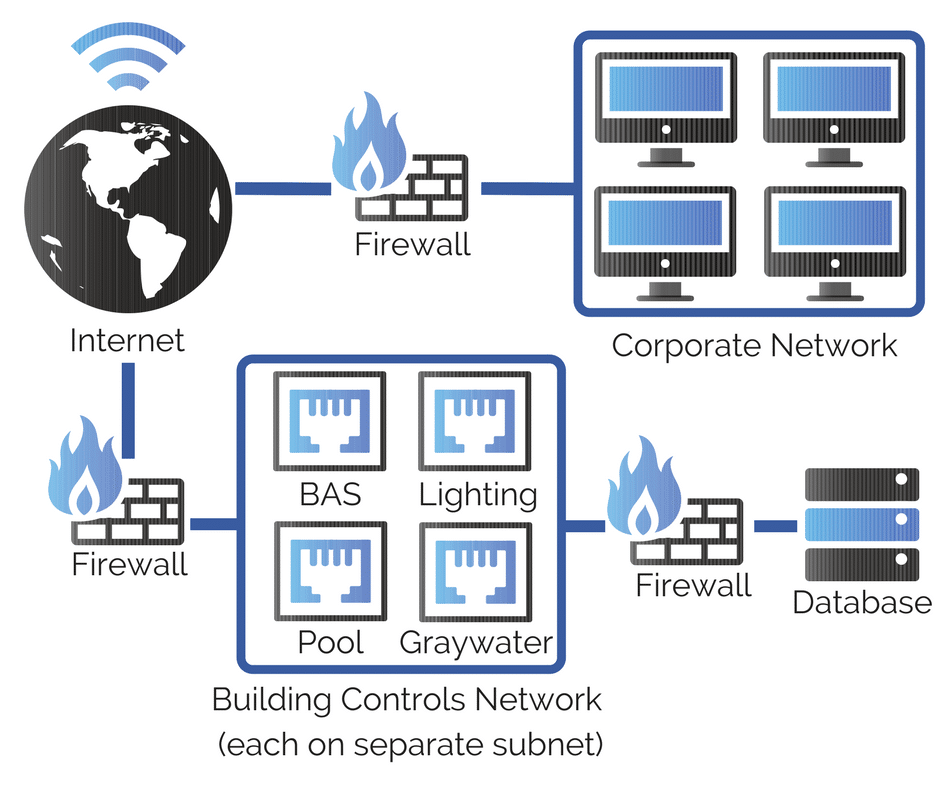

- Review the IT infrastructure, keeping in mind that any system that resides on a network can be compromised and therefore specify firewalls to reside in front of the master network connection and each subnet section.

- Locate control systems in a secure location. Schematic Design is the best time to set aside the real estate and dictate the resources to provide physical security. Consider measures for different systems because they may not be able to be co-located; this includes the BMS, the lighting control system, PV equipment, metering, UPSs, etc.

- Put a basic network architecture diagram on the architectural, mechanical, or audio-visual (AV) drawings. Architectural? Yes, because it is the set that will include items from all disciplines. The mechanical set could be used if the (mechanical) controls contractor will act as the systems integrator. Same for the AV drawings/subcontractor. It should show:

- An independent network for the control systems and a firewall to separate it from the tenant’s network

- Whether (or not) this network connects to the tenant’s network and internet (these are not the same things)

- A subnet for each control system (BAS and its components, Lighting Control Systems and its components, any other process or specialty equipment (graywater, pool treatment, etc) or any other device that is connected to the network (PV equipment, metering, UPSs, Power Distribution Units (PDUs), switchgear and any other electrical infrastructure)

- That the data repository for the control systems is separated from the control system and isolated with a firewall.

- Figure 1 of this document provides a detailed diagram of secure network architecture. We’ve simplified it in the graphic below.

Figure 1: simplified diagram of Secure Network Architecture

- Only specify vendors who:

- Have a history of providing legacy support for products and platforms; this includes both software, patches, and hardware.

- Follow best practices in cyber supply chain risk management. See this NIST publication for more.[1]

- Only connect systems and equipment to the internet if it is truly needed.

- Any system to which you can remotely connect is ultimately attached to the Internet and is therefore vulnerable.

- Ask the manufacturer why internet access is needed, then make your decision. Don’t just allow remote access because they suggest it.

- Specify a data diode or other physical firewall if software firewalls are not sufficient.

- Specify that remote access ports (i.e. telnet 23, http 80, ftp 20/21, tftp 69, etc) be turned off after the manufacturer has performed start-up and check-out.

- If the ports can’t be turned off, specify a strong firewall for equipment that must be remotely monitored by the manufacturer.

- Require that the commissioning provider verify these ports have been turned off! ![2]

- Any system to which you can remotely connect is ultimately attached to the Internet and is therefore vulnerable.

Mitigation

- Require any equipment with an IP-based controller to provide an inventory and network diagram of their equipment. This is so the Owner’s IT staff can create their own response plan.

- Specify that the supplier provide a patch and update schedule for the devices that you specify.

- Specify vendor support for legacy equipment for at least 10 years after the purchase date. These systems are capital expenditures and vendors should not be allowed to “obsolete” equipment to shirk responsibility for continued support.

Recovery

- Specify extra/spare controllers be provided for the Owner’s test and development center

- Security patches can be applied and interaction with other components can be studied before it is applied to the live system. Have you ever had a Windows update go wrong?

- Specify a separate copy of the firmware. Require that the BMS, lighting control system, and any other control systems provide copies of the code programmed at this site, not generic code. In the event of a breach or ransomware attack, the firmware and software can be replaced.

Guidance for Building Owners and Developers

- Because physical security is as important as IT security, you should locate control systems in secure locations. This applies to the BMS, lighting control system, PV equipment, metering, UPS’s, and similar supervisory control systems. Require automatic door closers on doors; provide HVAC or door louvers and exhaust if doors get propped open because rooms are too hot.

- Physically separate the BMS network from the IT network (i.e. separate servers)

- For equipment that requires internet connectivity and vendors that need to connect to control systems, require a Virtual Private Network (VPN) connection for remote access.

- Read and follow the recommendations of NIST’s Guide to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Security (SP 800-82).

- Use the CSET tool to create a plan for securing your ICS/OT infrastructure. Execute the plan.

- For new projects, get your IT staff involved early – get their security requirements and put it in the Owner’s Project Requirements (OPR), have them review the equipment specified and then the submittals.

- Coordinate the cybersecurity efforts of IT staff and facilities.

- Practice safe maintenance: Apply security patches regularly, just as you would physical preventative maintenance.

- Create a test and development center (i.e. sandbox) and apply patches in this environment before rolling it out to the rest of the equipment.

- Create a rescue/recovery kit with the firmware and software of your systems and store it off the network.

- Create regular backups of your BMS data and/or a separate partition to store BMS data and encrypt the drive. If you’ve created recovery kit, your software is replaceable, but your BMS data is not. By creating a backup, you’re protected. Even if attackers wipe/ransom your BMS programming, they will have to get through the encryption to steal the data.

- Monitor your systems to understand non-baseline anomalies (e.g. network scanning, controller re-flash, communication with an outside server) (Glasswire is a great tool for this.)

In our commissioning practice, we are going beyond mechanical systems to minimize risks to you, our clients. I know that this sounds like a lot of extra work, but with increased internet access, there are a lot of new risks that we’re not used to, and much at stake. I hope that by sharing these tips with you, you can take action to protect yourself, your clients, and your tenants from cybersecurity breaches. Once you’ve implemented these steps once in your design process, or in your building, it becomes part of your standard operating procedures. If we can be of assistance, please don’t hesitate to contact us at cx@kw-engineering.com

For further reading see:

- ICS-CERT Introduction to Recommended Practices in ICS Security

- NIST 800-82 Guide to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Security

- UFC 4-010-06 (UFC) Cybersecurity of Facility-Related Control Systems

- Whole Building Design Guide Cybersecurity recommendations

- NIST Best Practices in Cyber Supply Chain Risk Management

- Your Control Systems Have Been Hacked, Now What?

- Johnson Controls Guide to Cybersmart Buildings and accompanying presentation (NCBC 2017)

- Federal & State Security Standards for Connected Building Systems, a presentation by Bob Hunter at NCBC 2017

[1] At this time, this is more easily said than done. NIST supply chain cybersecurity best practices call for knowing what components are inside the equipment. This is so that vulnerabilities can be tracked and traced. Unfortunately, many manufacturers aren’t doing this. For example, ABB released a notification about processor vulnerabilities due to Meltdown and Spectre. A week after the vulnerabilities were made public, ABB did not know which equipment was affected. They issued a bulletin that gave a vague warning: “At the time of this publication, we are still investigating the affected ABB products. However, all ABB products that run on affected processors are potentially affected.” But just because they are not doing it, doesn’t mean you shouldn’t ask!

[2] Cybersecurity for building systems is such a new concept that the commissioning provider will not expect it to be there and will not look for it. Communication and coordination of this requirement is essential.